Feb Number 2

nº 2

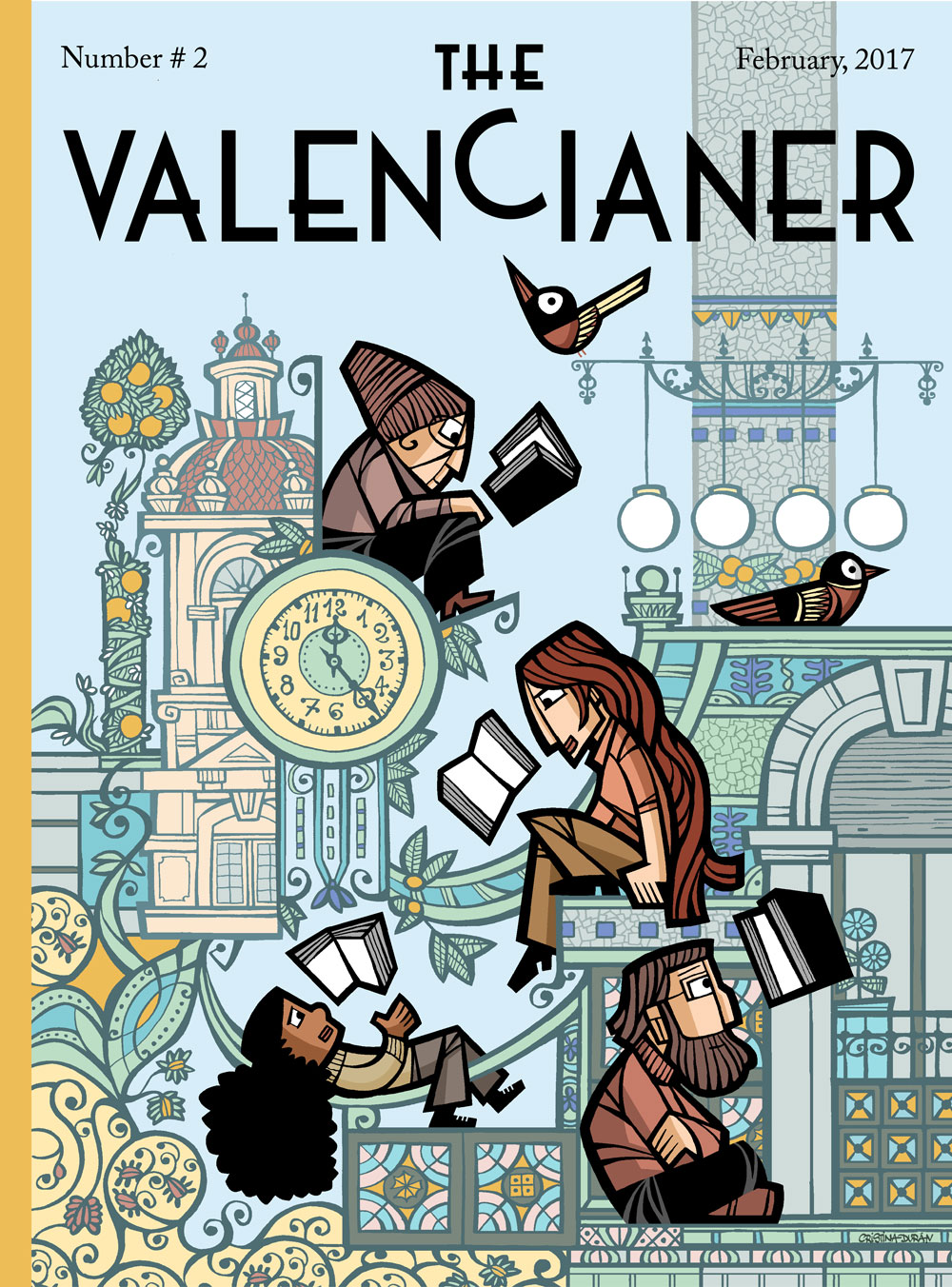

Cover:

Trencadís.

DURÁN

Cristina Durán, the author of the cover, was born in Valencia but lives in Benetússer, a place that has become famous because of the production of combs.

When Cristina read the celebrated bande dessinée “Barbarella” and found that her surname coincided with the wicked Dr. Duran Duran, she decided to dedicate her life to do good. In fact, when she ever draws an evil character, you feel like you should rehabilitate it.

She is an expert drawing impossible perspectives and puppets, but what makes her really proud is to have accomplished a lot of her dreams, like creating a great studio where she works surrounded by illustrators and designers who are her friends, having two daughters of different colors and being a renowned author of comics along his scriptwriter-husband Miguel Ángel Giner Bou.

In the last years the comics have interfered in her career as illustrator, which made her more poor but happier -as she says- because she has learned from the reactions and emotions of the people that read her comics.

In brief, Cristina Durán doesn’t know how to draw evil people. But be aware: her stories are a punch in the heart.

This is her website.

Stamp: ©Cristina Durán

PORCEL

Pedro Porcel is the author of Aunt Teresa’s Bar. He was born and lives in Valencia.

He loves the bizarre, the filthy, the pop culture and all the things placed in the limits of reality. He is well known as little grandpa, the pseudonym that he uses in his blog full of trading cards, awful movies, rotten comic books and infamous literature. His blog is a microclimate of strange odors.

But friends, this is just a smokescreen to hide his glorious past, when he was the coeditor of Arrebato, the most modern publisher of albums in Spain. He was also the co-founder of Continental and La Edad de Oro, the funniest bars in Valencia.

Pedro Porcel is an expert mixing duty with pleasure.

This is his website.

Stamp: ©Carlos Ortin

GARRIDO

Manuel Garrido is the illustrator of Aunt Teresa’s Bar. He was born and lives in Valencia.

He presents himself as an arts manager, art critic and illustrator, but today we’ll just focus on his graphic work. As an illustrator he chooses his collaborations on magazines, blogs and campaigns depending on the sonority of their names. Let’s see: Giant tiger, Infamous, Skeleton cities, No blood on my clothes, For whom my heart beats, Between the coffin and the suitcase, How I drew your mother…

When we proposed him this assignment we said that he came to our mind as the perfect illustrator for Porcel’s text. Manu read the text and started to worry.

–I don’t know what image I should project but you got it right: I love it –he said.

Garrido finds inspiration in the darkest side of Goya, in the most rotten side of Grosz and in the sickest side of Gorey. That makes a poker with the letter G.

And he still worries about the image he projects. Ja!

This is his website.

Stamp: ©Manuel Garrido

The epicenter of one of plenty secret Valencias was located in a narrow block with no more than three rotten and cramped buildings that perpetuated the general condition of the neighborhood. In the closest point to Plaza del Collado -where the last victim of the spanish inquisitorial fury was burned- there was a small ground floor with various lofts: the labyrinthine headquarters of the last valencian taxidermist, a delirious character who wrote pulp novels of adventures, went to hunt buffalos to Africa and dissected heads of bulls, deers and even entire horses, with his excessive and progressively rambling chat.

In the other corner of the block there were some cabins made of wood, full of old comic books, paperback novels of Corín Tellado, photonovels, newspapers, magazines from the past month and all type of yellowish papers. Veteran women with bleached hair, extreme makeup and long nails painted in loud read, administrated those faided containers of dreams and collective miasma, which in the beginning of the eighties started to decay unstoppably. Located in another hallway, without any exterior signs and behind some narrow stairs with room for only one person, there was a hippy flat reserved for the initiated who, between pillows spread on the floor and dirty carpets, consumed Moroccan tea, some beer introduced secretly and all kind of smoke, when smoking was allowed and also the quintessence of that sacred place. Next door to this unique tea house there was the winery Bodegas José Español, as you could read on the sign made of punched letters formerly golden, attached to the wall of the facade.

Aunt Teresa’s bar, as we knew it, was an anomaly of time and space, even for that Valencia influenced by a provincial legacy. It was an excrescence from postwar anchored in a different era. Inside Aunt Teresa’s bar, time flowed at its own pace. A wooden bar with marble, presumably white in better times, was illuminated by a wasted neon and a couple of bared bulbs. In the corner next to the entrance there was a door hiding the unisex toilet: just a hole in the floor. In the bar you could see a lot of wood, more dust, barrels of wine –not of many types nor abundant–, two or three domestic chairs, not any special furniture, flaking walls that were not flat anymore, high ceilings and, beyond the wooden bar, some kind of coquettish and rancid cleanliness.

Right there, flanked by a picture dedicated by Chanquete (one of those images included in the packs of cookies María) and by the picture of Pope John Paul II, served Mrs. Teresa. She was a small and old lady, eyes of dead ox, slow gestures, she was satisfied of attending that last refuge. In front of her there were a dusty frame with the sepia picture of a man with an ancient spanish face and a poster from the magazine Marca, showing the time when Valencia was champion of the league in 1971. Beneath those pictures, every afternoon you could see –sat on a sofa which seat was the perfect portrait of her butt– an old lady dressed in black, with various layers of mantillas and cardigans, all messed-up and crowned by her decreasing head. Agripina was her name, and she never moved or talked. She just looked from one side to another without anyone knowing how aware she was. At eight o’clock, Teresa yelled to send her to sleep, assisted by any drunk and supportive volunteer who helped her to cross the stairs that lead up to her bedroom.

The place was a bar, a wine shop and a house at the same time. You could perfectly imagine that below the place, hidden behind a folding screen made of wood and crystals that retain a lot of dust, there were a table stretcher, knitting needles and a television that was never turned on. Upstairs, in a wooden attic, there were Agripina’s and Teresa’s rooms. In front of the wooden bar, you could see the small but very loyal group of regular customers.

Wine, beer and soda –the only drinks that the bar offered– were consumed with heart and soul by professional drinkers. It was a multi-colored gathering of people that Marx and the trendy use to call “lumpen”, where a guy who worked as a switchman in a grade crossing represented the higher class in the pyramid. Among drinks, enchanting discussions and out loud voices, their favorite activity was playing spoof without rest, creating intense fights for a single peseta, followed by intense arguments about the investment of such an extraordinary sum.

Physical fights never happened, not because there weren’t reasons but because of the guardian presence of Mrs. Teresa, who once in a while –with only 1,50 meter tall– acted like an angry mother confronting and giving a good scold to anyone that deserved it. More than one time she ordered to put on his pants to some exhibitionist who wanted to show his disgraces. It was very famous the moment when she slapped the face of Manolo el Bufa, a dirty and happy boozer who used to rob to the first-time hippies that visited the Plaza de la Virgen. Being a poor but honest alcoholic who visited the bar was one thing. But being an unoccupied vagabond that appeated occasionally was very different; aunt Teresa didn’t like them at all. Punks, squatters and other contemporary subespecies didn’t entered the bar: it wasn’t their era yet.

Physical fights never happened, not because there weren’t reasons but because of the guardian presence of Mrs. Teresa, who once in a while –with only 1,50 meter tall– acted like an angry mother confronting and giving a good scold to anyone that deserved it. More than one time she ordered to put on his pants to some exhibitionist who wanted to show his disgraces. It was very famous the moment when she slapped the face of Manolo el Bufa, a dirty and happy boozer who used to rob to the first-time hippies that visited the Plaza de la Virgen. Being a poor but honest alcoholic who visited the bar was one thing. But being an unoccupied vagabond that appeated occasionally was very different; aunt Teresa didn’t like them at all. Punks, squatters and other contemporary subespecies didn’t entered the bar: it wasn’t their era yet.

Around 1986, more or less, aunt Teresa retired. The wine shop closed and its surreal espectacle dissapeared forever, along with my frequent visits to the place. The modernity, jealous and ashamed of its roots, demolished a great part of that prodigious and grotesque block. Nowadays, in the logic of our times, it only remains as a plot.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.