May Number 5

nº 5

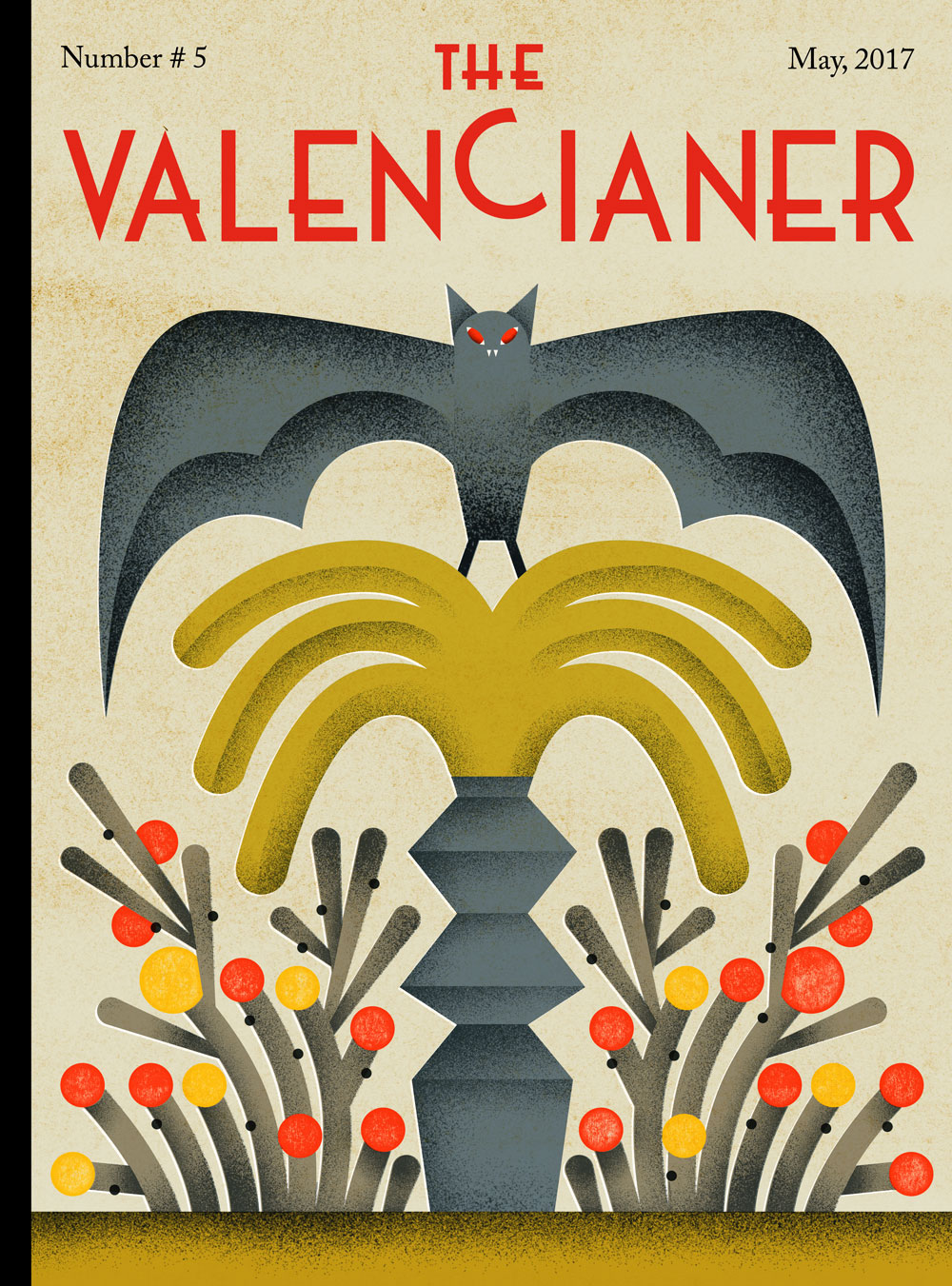

Cover:

The punished rat

MALOTA

Malota, the author of the cover, was born in Jaén, grew up in Yecla and she currently lives in Valencia.

Besides being a recognized illustrator, she is Doctor of Fine Arts. She is adored by students from a bunch of countries, magazines and some publishers.

She is the author of some memorable textile designs and graphics. The world of ceramic has no secrets for Malota. Her skill for screenprint and stamping in general is more than remarkable. She is a pianist and composer since her early years. She strongly believes that perseverance is the reason of her success. And she tap dances. Goddamn!

Her real name is Mar. And her real surnames, Hernández and Fernández, are the same used for the spanish version of Dupont and Dupond, the identical and surreal policemen that appear in the comics of Tintin. This may explain a lot of things, but probably not.

Perhaps we should believe in the tale of the perseverance.

This is her website.

Stamp: ©Carlos Ortin

GARRIDO

Manuel Garrido, the author of The inventor of the bikeplane, was born and lives in Valencia.

He collaborated before in The Valencianer (see number 2) in his role as illustrator. In this issue, he participates as a writer, a field that he experiences as an art critic writing numerous reviews and articles for blogs, magazines, catalogues, cultural supplements and in a radio show, with his section The banana of Warhola.

For all these skills and interests, he is known as the “man of Renaissance”, and also as “man of the fifties”… because of the way he dresses.

He has also written plenty of poems, short tales and a couple of novel attemps. In his own words, “… the fact that the majority of these texts haven’t seen the light -or have been closer to it as much as the wings of Icarus- has prevented the world to have another aspirant for cursed poet and absinthe drinker”.

Only as something curious, we can mention that he suffers from “glazomania”, a strange addiction to obsessively make countless lists of all kinds.

In this article, Garrido portrays an archetypical character from Valencia: the “shameless dreamer”, that person with double personality that, even being aware of his own scams, he needs to believe in them to feel innocent. A mix between a misunderstood hero and a scammer villain, a character well-known around here.

This is his website.

Stamp: ©Manuel Garrido

“In this great pond there´re very few protective ports where you will find refuge against the elements of fantasy and legends with more or less fundament”.

Juan Peñataro

History is composed by some small stories that, being more or less credible, show some evidence. Others are hardly provables and dance in the limits of fantasy, truth, legend and reality. Occasionally, a good story reappears too late in time to get the testimonies of the protagonists, and it only offers some press notes, some inconsistent information and distant memories from the family. Among these small but great stories, there’re a lot reflecting, from the beginning of time, the fascination and human desire to fly: the myth of Daedalus and Icarus, or the mechanical pigeon of Archytas, passing through the studies of Leonardo da Vinci and Giovan Battista Danti, arriving –for example– to the very first motorized flight in Spain (in Paterna, 1909) by Joan Olivert el volaoret. But what you’re about to read, dear reader, is the unknown story of Juan Peñataro Samper, a professional mechanical dentist and vocational inventor.

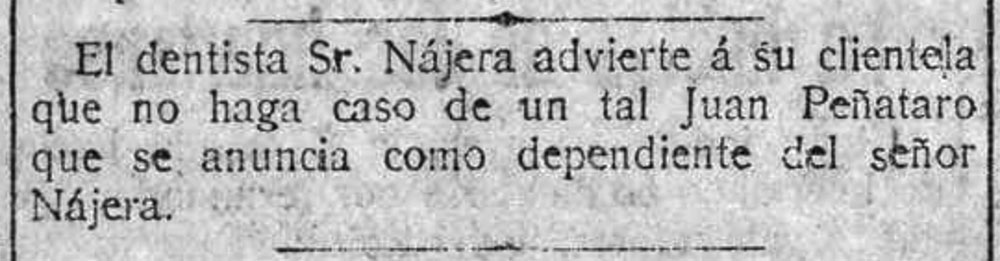

Juan Peñataro was born in Monóvar (Alicante, Spain) in 1891, and was a neighbor of the ancient Valencia of El Cid, until he died in 1946. He was a descendant of a lineage of italian boilermakers with the surname of Pignataro or Pignatelli, who established their home in the quarter of El Carmen, In Valencia. To get a clear idea of the volatility of our protagonist, there’re different versions that allege he was formed as an apprentice of a french prosthetist that lived in the Plaza de la Reina, or maybe he attended classes in the School of Dental Prosthesis of Madrid, or perharps in Buenos Aires. With such imprecision, it’s not strange to read in an ad of “El Pueblo. Diario Republicano de Valencia”, a newspaper of 1916: “The dentist Mr. Nájera warns his customers not to pay attention to Juan Peñataro, who presents himself as the assistant of Mr. Nájera”.

Great traveler during his youth, Juan Peñataro knew several countries from Europe and América, and he mastered up to four languages. In fact, it’ll be in Tandil, in the province of Buenos Aires, where he established himself as mechanical dentist in the clinic of Isidoro F. Tomatti, in 1911, as we know from a promotional ad where both professionals appear posing as stylish and good-looking men. In those days, the city of Tandil was popular because a huge rock was balanced on the edge of a hill, until –perhaps after many centuries or millenniums of immobility– it finally fell two months after Peñataro’s arrival.

Back to Valencia, he got married and had four children, two of them died at a very young age. In Valencia he established his own clinic of dental prosthesis, he lived comfortably –trying always to help those with less fortune– and he frecuented the intellectual circles, having a special friendship with José Martínez Ruiz Azorín. When the civil war ended, in a trip to Monóvar –his natal town– in 1942, Peñataro was arrested for saying “offensive words to the moral and authority”, and he was condemned for six months in jail accused of “assisting the rebellion”. After serving half of the sentence in the jails of Monóvar and Alicante (where he survived thanks to the cares of the women of his family), he left jail mentally affected, on financial crisis, and claiming that he saw a Marian apparition. In 1944, two years before his death, he was accused and fined for “the repeated intrusion in the dental profession”, fine that was cancelled after alleging that he was not in full use of his faculties and that in his house there was not any clinic.

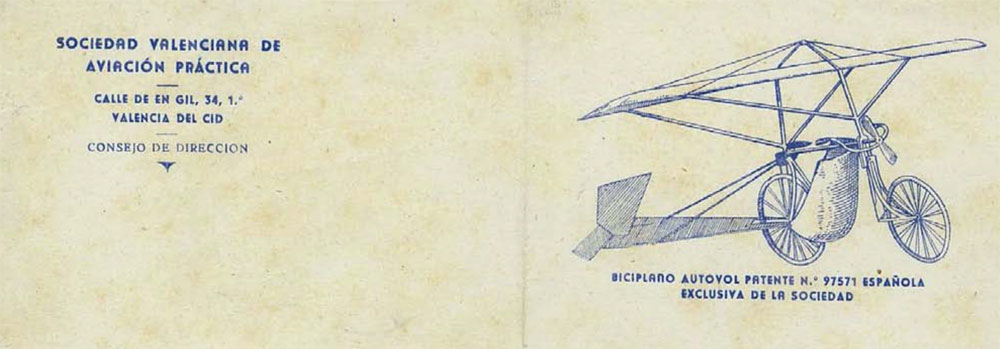

But if there’s something that stands out in the amazing biography of Peñataro, it is his role as an inventor. After creating an alloy for the making of dental prosthesis and a gas mask, he dedicated all his efforts to the bikeplane Autovol: a winged bicycle intended to demonstrate that “a man can rise and maintain in the air with his own force and without the help of an engine” (patent 97.571).

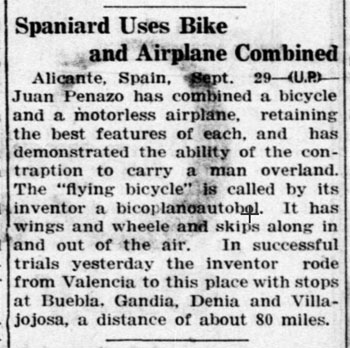

The Autovol becomes his main obsession and he puts all his strenght to demonstrate that it works. He delivers numerous speeches about the history of aviation and the greatness of his invention, speeches that are received by the valencian public with a mix of excitement and disbelief. He writes articles on press under the pseudonym of Juan de Vinalopó. He programmes exhibitions of his device all over the peninsula, and he intends to accomplish fearsome tasks such as an air raid Monóvar-Amsterdam mounted on his bikeplane, to cross the Strait of Gibraltar or to participate in the Olympic Games of 1928. There’re numerous newspapers that reflect intermittently his great deeds, between the years 1926 and 1933, with headlines such as “Sensational spectacle never seen before in Valencia” (El Pueblo), “Though hard to believe, a bike to fly” (El Heraldo de Madrid) or “Spaniard Uses Bike and Airplane Combined” (The Dekalb Daily Chronicle, Illinois).

However, there’re no proofs that those demonstrations took place. Little by little, the impatience to see the Autovol in action falls over the newspapers, divided in those who claim his success “applauded by thounsands of people” and those that consider his invent is a hoax and he is a charlatan. “Does it really fly?”, says the headline of El Día of Alicante, in 1927. Some years later, Peñataro would reappear in the press, reconverted in a sport events promotor (Autovol International Sports Company) with a festival programmed in 1932 in the airfield of the Malvarrosa –for the benefit of the University of Valencia, that suffered a terrible fire in may of the same year– where he plans to present “Miss Athletics”, the “rocketbike”, the “crazybike” and an “automata that will send light signals when it conquers the moon”.

Meanwhile, he moves heaven and earth to promote and look for sponsors for his bikeplane, and he contacts with every imaginable company, from the Air Force Ministry of Spain to the Patriotic Spanish Society Union of Buenos Aires; he even puts an ad in the newspaper asking for economical support in the name of the Valencian Society of Practical Aviation –which he also funded– demanding the use of an extension of 2 square kilometers in the area of La Albufera. In 1940, the Air Force Ministry finally answered his letters with a detailed study where, among other jars of cold water, he was informed that his bikeplane was too heavy to rise in the air, that possibly a similar device could work with a pilot with a better physical resistance than his… and that his invention was just an hybrid mix between a plane and a bicycle, with the inconvenients of both but without any advantage.

Juan Peñataro died the 11 of november of 1946, a month before the birth of his first granddaughter, and he was buried –apparently at his own request “for his political ideas”– in a mass grave in the cemetery of Valencia.

In 1972, his remains were moved into the nich of one of his daughters. Among his abundant files, one note without date was found: “I managed to take off and to time a flight of forty-eight meters wide and eight meters high”.

Manuel Garrido Barberá.

Art critic,

illustrator,

manager of APIV.

Great-grandson of Juan Peñataro.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.