Nov Number 10

nº 10

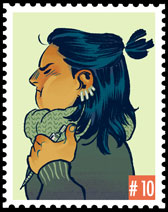

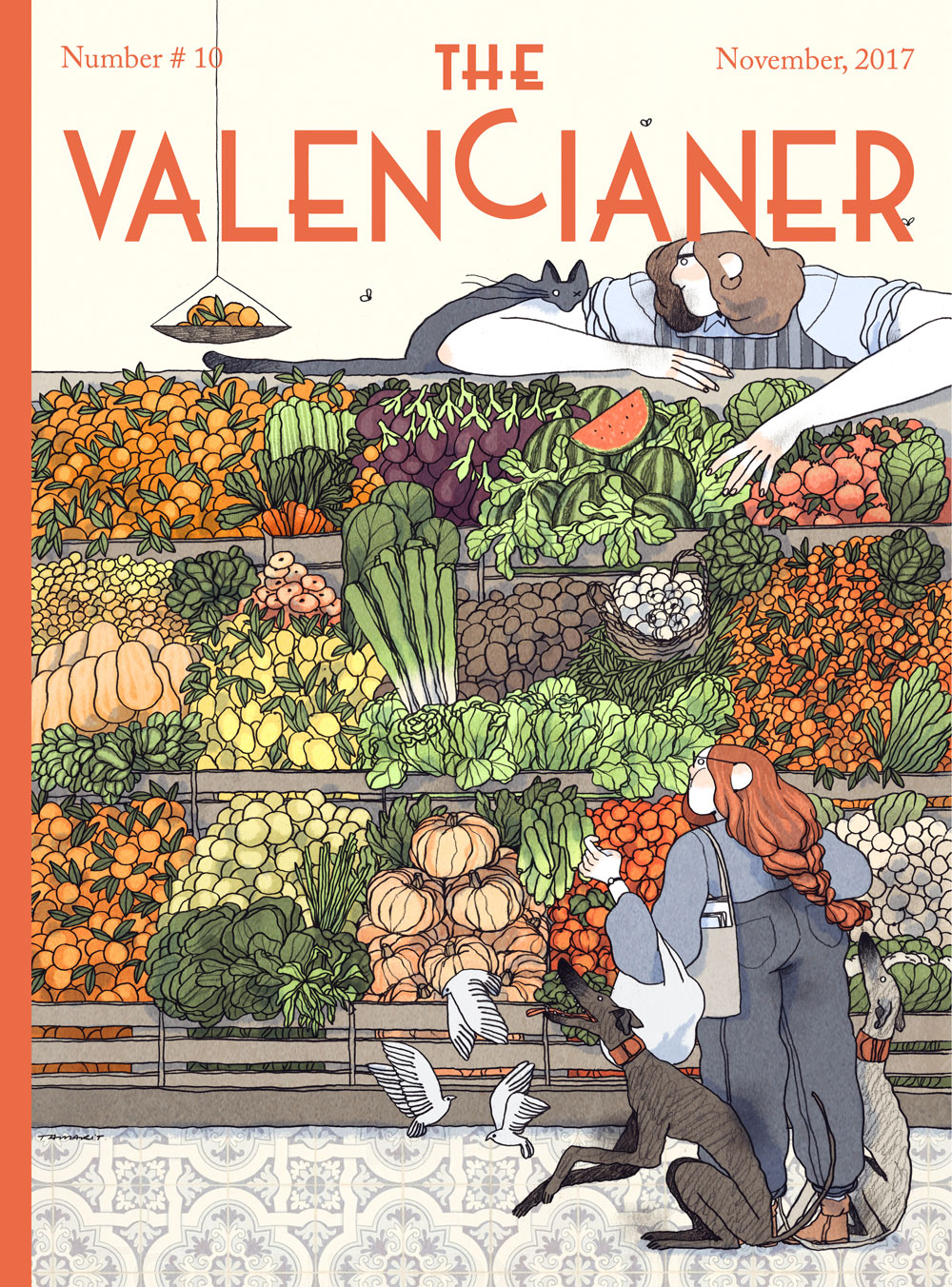

Cover:

Clementinas

TAMARIT

Núria Tamarit, the author of the cover, was born –as anecdote– in Vila-real, but lives in Valencia.

It is an indomitable force of nature in terms of drawing and style. It’s fast and good. There are those who have seen her drawing, in the middle of many work meetings, three or four absolutely wonderful complete pages, while she was aware of what was going on there.

Despite being an influencer on Instagram or Behance (with more than 1000 likes for each drawing she publishes), she is very demanding with what she does, arguing her self-criticism really well, while working at home listening to mostly instrumental music.

Of course, she does not usually draw in pajamas, that habit of doubtful taste so popular among artists.

Those who know her enjoy her fine and intelligent humor, which always plays with the interlocutor’s complicity. It is clear that this ability knows how to transfer it to his art.

And attention, if you write his name, never forget the accent mark. It’s an advice.

This is her website.

Stamp: ©Xulia Vicente

KUBALA

Lalo Kubala, the author of Tarzan, was born and lives in Valencia.

With frank and contagious laughter, his appearance is, according to the day, a mixture between Latin dandy and truck driver. Between capo of the mafia and orange worker. Between croupier and beatnik writer.

This is undoubtedly given by the disparate of his three main occupations: in the morning he is an art teacher, then he spends the afternoon drawing humorous vignettes (with an autobiographical and biting style) and the night is dedicated to rock & roll with Los Mocetones, the mythical group where he is a singer.

Lately, we have to add to his random activities the facet of actor, in which highlights his interpretation of the money junkie (20″) and the eloquent political speaker, especially from his watchtower on Facebook and his book Barbaritats Valencianes, of which he is co-author with Xavi Castillo.

Oh! And a costumbrista narrator for The Valencianer.

His biographers believe that the origin of his funny writting lies in being the son of a large family, with a lot of brothers and sisters.

Legend says that once he was invited to a high society wedding and the next day, with a huge hangover, read the review of the wedding in the “Echoes of Society” of the local newspaper, in which the wise writer wrote: “Among the guests, as well as eminent industrialists and the living forces of the city, was the famous soccer player and national coach Ladislao Kubala.”

This is his website.

Stamp: ©Gerard Miquel

RUBÉN GIL

Rubén Gil, the illustrator of Tarzan, was born in Alicante, but lives in Dènia.

Since he is a few words man, he needs to draw to express himself as much as the air he breathes. If you do not believe me, take a look at his self-portrait.

Rubén is an exceptional case of chemically pure comic’s artist who moves like a fish in water in the superheroes universe, and who is also capable of getting out of the sequential world and face political content illustrations in which, with a single image, hits directly on the reader’s waterline.

Proof of his disparate capabilities is that, having specialized in drawing and animation, he has been making a living as a sculptor for many years.

Maybe that’s why his illustrations are powerful, hard and strong. They contain heavy elements, some chemistry, a bit of stone and some history.

Thus, Rubén draws in the same way he cooks, taking what is in the fridge whatever it is, and with a skilful use of spices he gets a perfect dish.

But I would not like to give of him a wrong image: we know that every time he watches the first 10 minutes of the movie Up, he cannot hold back a tear.

His favorite word is abyss. If you know him a little, that won’t surprise you.

This is his website.

Stamp: ©Rubén Gil

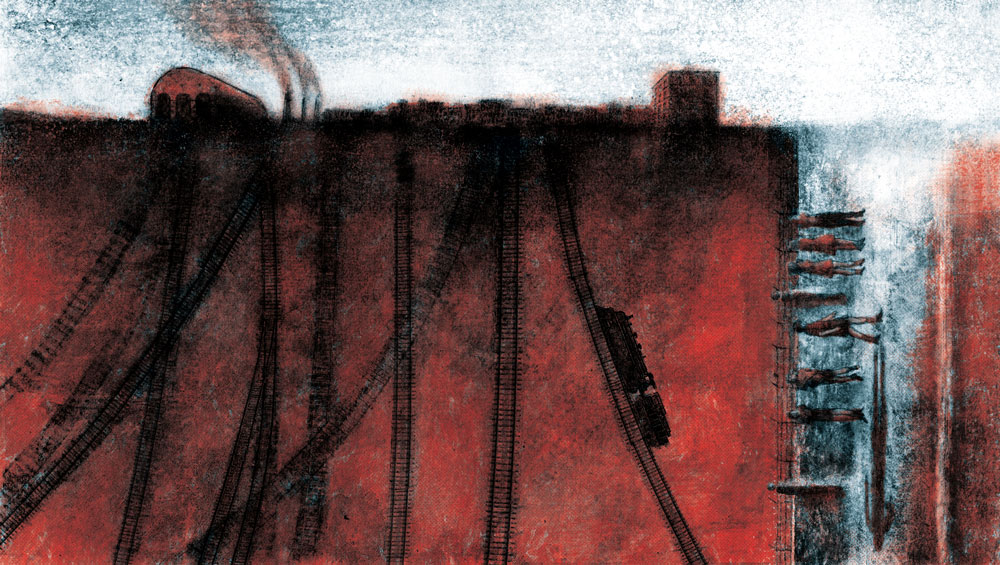

I am a suburb’s Valencian, from the river’s margin located outside the city. I was born besides the Alameda, in La Cigüeña. I grew up in the avenue Aragón, when it was still occupied by the railroad tracks of the former Station of the same name. The abandoned garages of Renfe were “protected” with a fence that surrounded the old train installations. A fence, certainly weak, that had multiple holes that allowed the kids of the quarter to play around in the obsolete wagons that were still there.

Although the fence didn’t accomplished the mission to protect the train heritage (reduced in that time to an apocalyptic vision that didn’t recall its splendid past), it was in fact a natural frontier that separated us from the quarter l’Amistat and to the maritime quarters, considering the enthusiastic movility of a former ten year old kid.

In the south, the river Turia, with a stinky and rachitic caudal, was the frontier that blocked our occasional expeditions to the center of the city.

In the north, a thinly populated Blasco Ibáñez and the friendly universitary zone, allowed us to reach easily the zone of undeveloped lots and the vegetable gardens that separated the capital from Benimaclet.

For our juvenile and explotatory instinct, we had all the west district: the quarter of Exposición and the posh zone that was growing behind the Chalets de los periodistas, besides the Jardines del Real, the exclusive Tennis Club of Valencia and around Jaime Roig.

These were not especially dangerous places in the city, because they were far away from the lumpen, a place that surely would have provided me with more scabrous childhood memories. But all of these quarters, with their tricky dullness, were -in fact- full of mythical individuals…

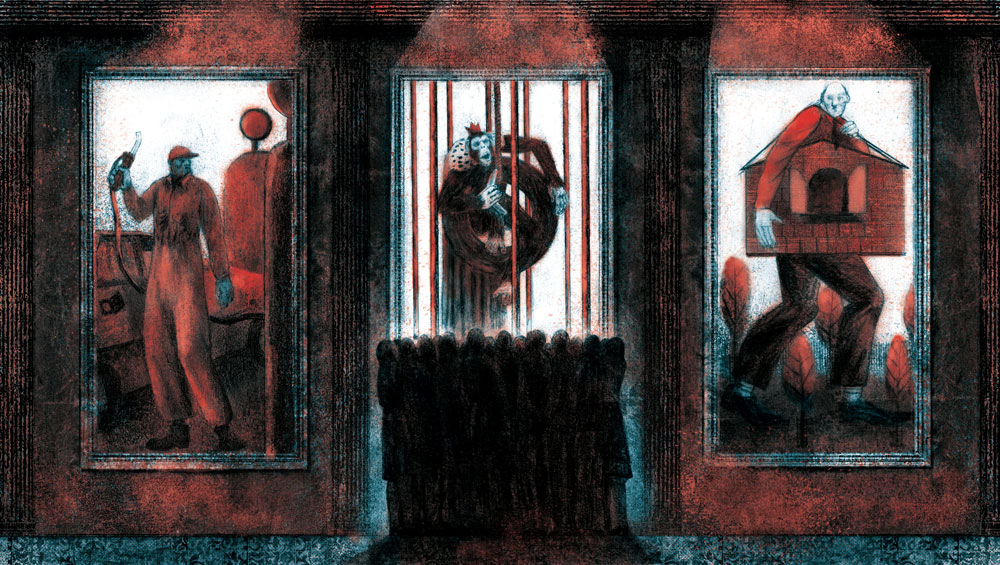

In the north, at the gas station of Primado Reig crossing with Jaime Roig, worked an african man –I think he was from Guinea Ecuatorial– who made the station look like the most exotic place. Let’s place ourselves in the seventies: at that time, for the kid I was, under 10 years old, I hadn’t been so close to a black man except from all those Christmas Baltazhars with their skin painted, acting in the big stores and in the Three King’s parade. To see a black man in a short distance, although “protected” behind the car’s window, was a real impact for a kid in a country of emigrants, a country that was in the tail of almost every iniciative in Europe.

It sounds very political incorrect nowadays, but I assure you that looking to this man working just a few centimeters away, I felt like having a Safari Park near home.

“The Giant” was another legendary being that lived in the region. A 2,33 meters guy that possesed the title of the tallest man in Europe. His name was Jaime Clemente and he worked in a kiosk behind the Tennis Club. Apparently, some basketball team wanted him because of his tallness, but his colossal size caused complications that impeded him to become the spanish Sabonis.

It was an an amazing experience to see such a colossus walking down the street. The size of his shoes was the same size of the Geyperman’s war tank that I got as my First Communion’s present. Although his way of walking looked clumsy, his sparing rhythm had some elegance. At his side, you’d better move fast, one of his steps was ten yours.

It was even more incredible to see him inside his kiosk. It was hard to imagine how his titanic dimensions could fit in such a small cubicle. With his back arched and his neck twisted he had at hand all the products. And it was really amazing to see his hands giving me the change. I could easily take a nap lying on them.

Very close from the kiosk there was the park Viveros, and inside that small Valencian lung there was the Zoo, that opened the next year I was born. During almost 50 years of the existence of the zoo, the only animal that didn’t abandoned its category of “provisional” was one of the most fascinating characters of my childhood.

His name was Tarzan, a chimp captured in (again) Guinea, who arrived to Valencia in 1965, together with a bunch of animals to inaugurate the “house of beasts”. Tarzan was 3 years old when he landed in Valencia and died 35 years later, becoming one of the most celebrated figures of the Capital of Turia… despite passing his whole life behind bars.

My father, barely visible during weekdays, tried hard to look like a devoted and caring father on sunday, releasing my mother from the exhausting energy of 8 children and taking us for a morning walk. The park of Viveros was the habitual place to spend the sunday with the family, and the zoo was our favorite destination. Since it was the only zoo we knew, we were unaware of its shabby instalations and poor collection. But in that trashy Ark of Noah something was clear: Tarzan was the fucking king.

The most famous chimp in the Gulf of Valencia was a big celebrity, the unquestionable star of the zoo. There was always a bunch of visitors piled infront of his cell, ready to enjoy his tricks. Tarzan was fluent in Latin and learned how to get rewards after his performances. He oscillated from moments of apparent apathy to frenetic activity, like a monkey full of dexedrines. His euphoria provoked a massive enthusiasm. In those moments of madness, the chimp swung himself rapidly on the tire suspended in the center of his cage and screamed like a possessed, then he leaped on the bars and shook his body upside down while he made insane faces. Finally he used to pick up a rotten fruit or a piece of shit that he threw to the people. His crazy happening ended in a supreme state of calmness where he released his hand from the bar and asked for a banana or a sweet.

It’s needless to say that most of the people that returned to the zoo were interested in the progress of the chimp, especially when he got mad. My father was a skilled specialist in making Tarzan angry, and he enjoyed it like a monkey. And like the person that throws the stone then hides the hand, my father knew very well how to cover up himself when the fury of the chimp announced the next missile.

But little did he knew about the astuteness that Tarzan had gained after several years analizing the visitor’s behaivor. I believe that after our regular visits and thanks to his intelligence, the chimp knew my father and was waiting for him. One sunday, when we arrived to pay our familiar respects to the honorable chimp, my dad put himself infront of Tarzan and started his ritual of provocation, waiting for an explosion of madness and for our collective enthusiasm. This time Tarzan didn’t react as usual. Instead of screaming and jumping on the deck suspended in the roof, the chimp walked away to the corner while my father continued with his provocations, unaware of the surprise that the king of the zoo had for him. Because of the darkness of the place where the chimp was, we couldn’t see clearly, let alone anticipate any turning point in the script. The skilled chimp pooped on his right hand, then walked quietly to the bars where the unguarded agitator was, and with an extraordinary aim and strength threw his shit to him.

The missile made a mess on my father, landing in the left part of his chest like a sweet carnation. We were shocked, without daring to make fun of our father. But the chimp put his face among the bars and staring at him he drew up a malicious smile.

My father cleaned up the “medal” with his handkerchief and with the greatest possible dignity. We went back home in silence, and never again saw him torturing any other animal.

The 11 of september of 2000 Tarzan died. The emotional impact that the Valencians suffered because of his death can’t be compared with the one that the New Yorkers experienced one year later. But, at least in a simbolic degree, we also felt like orphans. For Valencia, Tarzan became a symbol as important as the Twin Towers. With his decease, some part of us dissapeared too.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.